Playful Decay and Contingency

Some thoughts on Yuki Mohri's 'Compose' at the 60th Venice Biennale

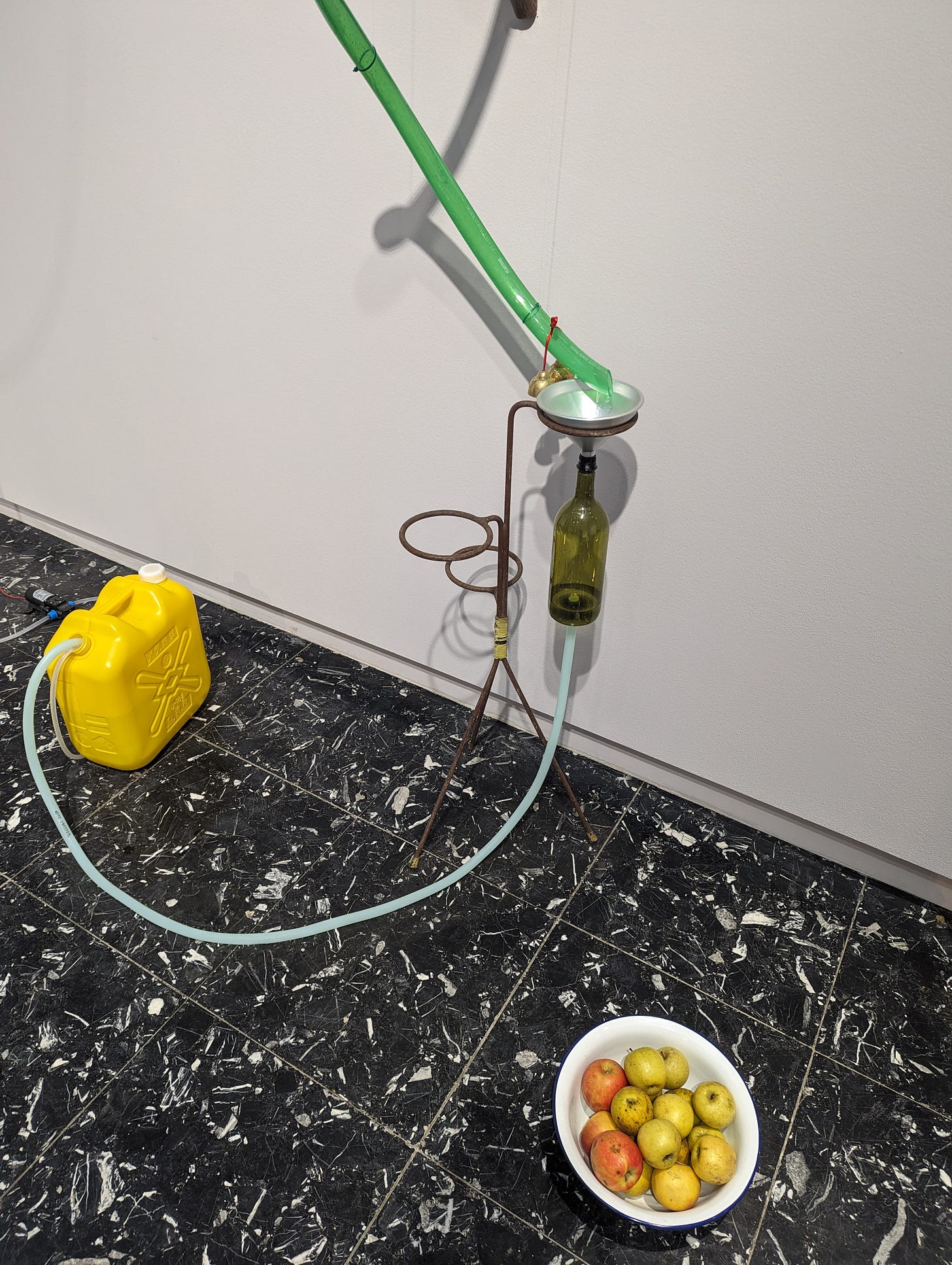

Yuko Mohri, Compose, installation view, 2024. Photos by me.

My first glimpse of Yuko Mohri’s work was beneath the Venice Biennale’s Japan Pavilion. Weary of walking, I’d been looking for a place to sit, and there happened to be a pleasantly minimalist bench beneath the structure. I sat on it and looked in wonder at the cords and subsequent bulbs as they spilled through the central opening to the room above, drawing attention to the unique architecture. The gentle pulse of light was hypnotizing, and yet demure and ambient, simultaneously asking for my attention all while fading out of focus. This playful conversation between awareness and atmosphere continued with the rest of Mohri’s installation, in both sight, sound, and smell. The work, titled Compose, could just as easily be an aural plein air impression of the ocean as it could be a readymade city street, or even a postmodern vignette of the subways from which Mohri gains her material inspiration. The entire work is a call to attention, a soliloquy of responsibility.

Upon entering, the viewer is met with an eclectic chorus of sensual movement–the sound of whispering drums, dripping water, tapping, brushing, and humming, ringing tones, the tangy fumes of rotting fruit, and the sight of almost imperceptible movement in the objects making up the installation’s visuality. Mohri uses a host of objects, gathered in Venice itself, to create kinetic post-minimalist mechanisms. Some are powered by electricity, while others draw their kinetic movement from fruit, wind, and water. Thin tubes, pumping water, stretch across much of the space, connecting one mechanism to another. Lightbulbs hang from black cords, stretching from beneath or behind various articles of home furniture, like coffee tables and dressers. Upon these furnishings, Mohri has placed fruit. The fruit’s electrical signals are monitored by wires, and converted into signals by a simple computer program created by the artist. The light bulbs, and sound installation, are controlled by the transient electrical pulses of the decaying fruit. An ambient soundscape of lush and chiming notes floats throughout the work, joining the clattering of the other kinetic mechanisms to bathe the viewer in sound. Mohri makes full use of the Japan pavilion’s stunning architecture, allowing her mechanisms to interact with its brutalism directly and playfully.

Walking through the installation becomes a meditation. My senses were wholly captured by the blossoming drones and murmuring objects. I stayed in the pavilion for over thirty minutes, listening and watching. I felt consumed by the place like I’d never been consumed by any other work–totally focused, yet oddly passive. Mohri drew me into a state of timelessness that was characterized by the passage of time, by the movement of objects through their own environmental chronologies. The skill of such work is evident in Mohri’s selection of objects (which she gathered from within Venice itself) , and in her self-consistency in composition. It would be incredibly easy for a lesser artist to slip into either obnoxious minimalism or obsessive maximalism, but Mohri walks a tightrope between the two with ease. The mechanisms are sparsely spaced, giving each other room to articulate themselves clearly–and yet there is still an abundant sense of ecological interconnectivity, as if to remove even a single piece of fruit might cause the entire contraption to dissolve like so much debris. This precariousness defines much of the experience. It seems, at times, that the sound must cease, that the lights must go off at some point. Yet this does not happen until the gallery attendants pull the plug and shut the door. Compose cannot avoid comparison to ecological environment, because it is far more than an allegory of it. Mohri has successfully communicated the nature of ecological biospheres through a language of illustrative, gestural sculptures and post-industrial, minimalist aesthetics.

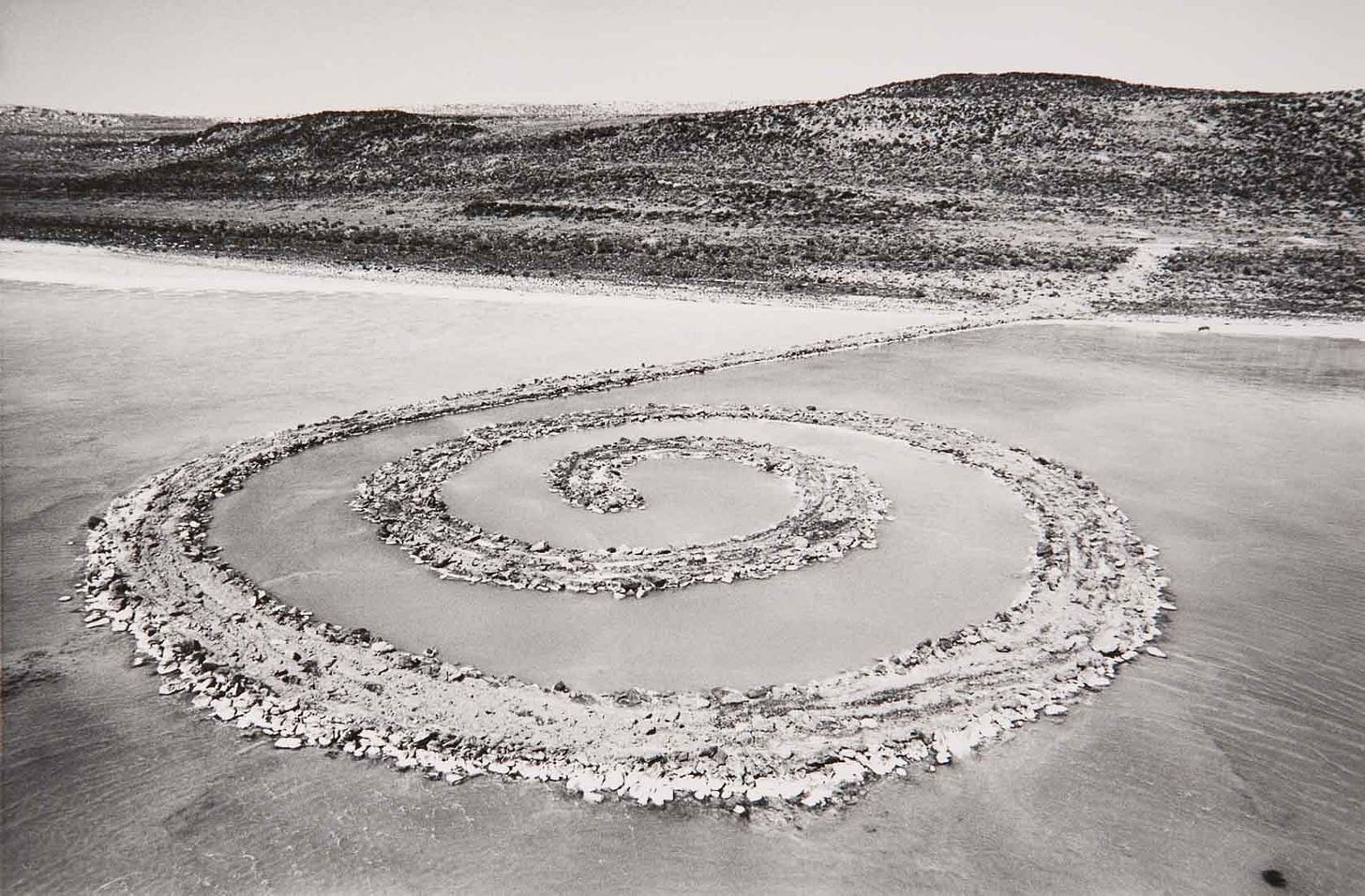

A dialogue between Compose and the earthwork (as proposed by artists like Richard Long and Robert Smithson) is helpful when we’re considering environments. Smithson’s Spiral Jetty is one of the most well known instances of American land art.

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, 1970, Great Salt Lake, Utah.

It uses temporality, contingency and embodiment to great effect, creating a vision of the monument beyond power or domination. The idea of ecological action versus inaction is evident in the very concept of the work. The fact that it becomes a feature of the landscape, rather than a structure upon it, makes Jetty a conversation about place’s efficacy. Jetty activates the body in its accessibility–it is open to the agency of its viewer. It also sensitizes our bodies to place as an active form, a gestural spatiality. The work changes over time, eroding and flowing with the lake in which it exists. A sort of ‘drawing’ happens as the work is drawn out of itself, it becomes less like architecture and more like skin, flexible and tensile, but soft to the touch of time. Mohri, precisely, is drawing out in Compose. The rotting fruit is drawn out of itself as its ‘fruitness’ is confirmed by its actual dissolution–in a Heideggerian twist, it is the ‘death’ of the fruit that lends it its quality of being. So too, does the viewer become more sensitive to the placeness of Venice as the installation hums around them. A spiral circuit of passive action makes us feel the ecological weight of time. Mohri has negotiated a place for her viewer that exists through the almost literal drawing-out of layers in human bodiliness and industry. The second life of her readymade materials is a language of spirals.

This language, and this environment, are ontologically based around a tension between action and inaction–similarly to much of the work of the Abstract-Expressionists, Compose is the intersection of intention and contingency. Mohri’s intent is abundantly clear, her hand is evident in the work’s internal logic, and yet it hums with the random, the unspecific; it becomes a wonderfully ephemeral orchestra of interstitial movement. The twitching tubes remind me of the subtle tremors that our veins and nerves experience, and the abrupt crashes and thumps from the drums is like the growling of our stomachs and bowels. Sitting with the art is like watching your body become suddenly, angelically exterior, as if the physical space of the Japan pavilion had become a sort of thumbprint–an index of the body. Mohri encodes the body into place like a weaver, layering and entwining even as she creates a cohesive image. Her interaction with architecture is key to this; she regards conventions of wall, floor and ceiling as neither here nor there–by this I mean she refuses to either wholly ignore or wholly invoke them. Place, of course, is a mechanic of Compose, but it is also the recalcitrant boundary of our experience therein. In the course of the work, it is almost as if Mohri is painting space with space.

Again, the sense of spatiality here is given credence by its real connectivity. The visual and kinetic precarity of the Calder-esque sculptures tells us how dependent the work is on itself–and yet it refuses to collapse. The pulsing movement speaks to the body as a contingent wholeness. In spite of its shuddering, groaning, pulsing complexity, the body miraculously retains itself–and in some sense, Mohri works this miracle anew through the aural and the kinetic. Mohri, in the exhibition book for Compose, says that she wanted to “...negotiate with the city of Venice.” It is precisely this idea of negotiation that colors Mohri’s gesture and composition. The miracle of the work is its delicacy, its argumentative intricacy. The Ecclesiastical notion of ‘ashes to ashes, dust to dust’ is made paradoxically concrete–although it is fading away (decomposing), we know that plastics and machines will not decay for hundreds of years. The fruit rots in real time, and the water drips away, leaving indexes of sound and smell as they do. Electricity acts as a sort of cyborg index, augmenting the decaying with industrial gesturality. The process of negotiation is seen in this vision of decay. Mohri considers Venice as a clash of nature and industry–the floating city is in a constant state of tension, wrestling with the very parameters of its existence. In Compose, wind and water affect states of being–so too does wind and water inform Venice’s own ontology. The mere existence of a city upon water is already a war between convention and decadence. A city, in its nature, is a product of earthy firmament–and yet Venice is a product of flows and motion. Where a city like Rome reflects the weight of its foundations in earth and history, Venice actively fights fire with fire (so to speak). Water and wind, the elements of the sea, cannot be countered with weight–this is a recipe for shipwreck and drowning. Rather, Mohri’s Venice encounters the unsurety of the sea with an elastic spatiality, a circuitous and flexible sensitivity to its surroundings. Spatiality is connective as a sort of gestural sketch. The construction of Compose is a sort of place-drawing, as if Mohri were making a lithograph print of industrial responsiveness. The question that she asks in this is simple, then: where does the body end, and the machine begin?

Destruction and creation become fused into a unique dialectic here. Spatiality expands and contracts through the ambient soundscape, and we suddenly become aware of place-qua-movement, place filled with motion. There are elements of postwar Gutai in the playfulness that Mohri brings to these questions, as well as the contingency of the gestural act. The Gutai movement’s commitment to contingency will always be, to some degree, a similar question of the bodily and the industrial. Although Gutai is less committed to the vision of the industrial as espoused by Mohri (if at all), it retains an implicit consideration of the complex and hybrid ontology that supports post war industrial modernity. Shiraga’s Challenging Mud (1955) conveys gestures beyond mechanics–he forgoes the brush and the canvas in order to paint with a sort of purified painterly expression, avoiding technique in order to address painting’s ontology.

Kazuo Shiraga, Challenging Mud, 1955, installation and performance.

The body/industry dialogue becomes circuitous for Shiraga, a revolving door of gestural energy. Painting as a sentiment of being becomes so clear for him, that he can wrangle necessity and contingency into a single whole, that is, a circuit. The idea of things ‘necessary’ and ‘unnecessary’ which informs the construction of the utilitarian, industrial era becomes non-linear—a loop, a spiral. This circuit is thus predicated on play: authentically contingent action, necessarily chosen but teleologically ambiguous. Mohri, similarly, is playing with the tense gap between bodies and machines, between that contingency and necessity. Place is her brush, and kinetic sound her paint. The peculiar drawing she does is a gestural exercise in interstitiality. The structure of Compose is the structure of the spiral–continuous movement, redirected at itself, and yet eternally moving away from its origin (or towards it!). This dance of decay, for me, is a sweet and humble address to the body. Mohri asks not only for our sense-ability, but for our response-ability: Compose is a remarkably active question, one that we might answer with the simply currency of attention.